Author: Yilmaz Algin (PhD cand. in Law Studies, Germany)

Original article in German, translated by: Rojda S.

“But the Ezidis call their language “zyman e ezda” (the language of the Ezidis)”,

Ernest Chantre in “Notes ethnologiques sur les Yésidi” in 1895, Turkey.

Since the genocide began in 2014, the Ezidi community has been the subject of countless discussions. On the one hand, because their religion and culture are still foreign to most people, on the other hand, because the obvious lack of information about history leads to frequent discussions about the identity of the Ezidis. Young Ezidis and Kurds, active on social networks, in particular, regularly discuss the ethnicity of the Ezidis and their language. Often there are opposing, hostile views, especially when some Ezidis insist on the term “Ezdiki” as the name of their language. But does it really exist? This question will be pursued in the following.

Mother tongue and sacral language

The native language of almost all Ezidis as well as the sacral language of Ezidis is the language designated as Kurmanji (Kurmancî). Nearly all Ezidi prayers, hymns (Qewls) etc. have been handed down in Kurmanji. In this context, this language has a special meaning for the Ezidis.

Kurmanji is regarded by Kurds as a dialect of the Kurdish language, whereby Kurds usually assume the existence of only one Kurdish language, which is divided into various dialects and vernaculars. However, there is also the view that Kurmanji is one of several independent Kurdish languages.

In particular, but not exclusively today’s Ezidis from the post-Soviet area use mainly the designation “Ezd(î)kî” for their language. The word “Êzdîkî” is composed of the root “Êz[î]dî” and the suffix “-kî”. The suffix “-kî” has the function of adjectivating the root of the word. Translated “Êzdîkî” thus means “Ezidi”. Thus it turns out that with “Kurmanji” (Kurmancî), “Êzdîkî” and “Kurdish” (Kurd. “kurdî”) there are three so-called glossonyms, i.e. names of this language, which are used.

This at first seems to be a completely banal statement, but already at this point the problem begins: There is a great intolerance towards the use of the glossonym “Ezdiki” – this term is vehemently rejected among others also by intellectual circles of the Ezidis who are mostly Kurdish-nationalistic. It is often excessively opposed to grant the Ezidis this designation for their language. The reasons for this and the social excesses this issue has taken on will be examined in more detail in the following for the first time.

If Ezidis from the post-Soviet area use the glossonym “Ezdiki” as a designation for their language in public, there are often negative reactions only on the basis of the use of this term. These reactions come from Kurdish nationalist circles, among which are often Ezidis who were socialized Kurdish natonistically. They consider the term “Ezdiki” as an attack on the national unity of the Kurds. The debates and arguments resulting from these opposing views, which are often ideologically motivated, make it difficult to objectify the discourse. A general rejection is expressed, for example by sentences like: “Such a language does not exist”, “that is Kurdish and not Ezdiki”, “if you want to speak Ezdiki, then look for another language than Kurdish, because that is ours”, or mockingly: “If you speak “Ezdiki”, the others speak “Muslim”?

There is a number of such constantly repeating behaviour patterns, which are not to be presented here conclusively. The argumentation is sometimes more complicated when political activists, journalists and intellectuals – even Ezidi professors – express such or similar negative views. Other Ezidi intellectuals have so far kept themselves out of this discussion altogether, because the Kurdish side has labeled dealing with this topic alone as betrayal or separatism.

The general tenor can be summarised as follows: The Ezidis should renounce their own designation of their language in favour of a higher goal; the Kurdish nationalist unity. The Ezidis’ own designation is seen as a danger of a national feeling among the Kurds which is still very fragile today.

Does “Ezdiki” exist at all or is it a politically and ideologically motivated neologism? Only through a thorough clarification a consensus and thus an end to ideological disputes is possible.

Language and glossonym

In the discussions it can be observed that the opponents of the term “Ezdiki” do not conceptually differentiate the language itself on the one hand, and the name of the language (the glossonym) on the other. The sentence “You speak Kurdish and not Ezidi” can be understood as contradicting the assertion that Ezidi is another language than Kurdish, or as contradicting the assertion that the glossonym, hence the mere designation “Ezdiki”, does not exist, but only “Kurdish”. What exactly is claimed or meant is almost always left unclear, probably because the claimant himself is often unclear about what exactly he means. In fact, first of all, “Kurmanji” and “Ezdiki” are glossonyms, i.e. names of the same linguistic variety. One and the same language may well have different glossonyms. This is nothing unusual. For example, “Bosnian”, “Serbian” and “Croatian” are different names for the same language. In Pakistan the term Urdu is used whereas in India the term Hindi is used for the same language. These are examples where different groups use different names for the same language spoken by all these groups themselves. The use of the glossonym “Ezdiki” is not “wrong” simply because other groups speak the same language using a different name for them. It is not unusual to have different terms for the same language.

So do the Ezidis speak Kurdish?

It is often said that Ezidis speak “Kurdish” or are “Kurdish-speaking”. Because, as mentioned, many Ezidis use the term “Ezdiki”, it is questionable whether this statement is correct. For example, it would be very unusual to claim that Indians speak Urdu or that Pakistanis speak Hindi. The same applies, for example, to Serbs and Bosniaks regarding Serbian and Bosnian.

Even the question of how the language “Kurdish” is to be defined, in particular whether Kurdish includes several languages or different dialects of only one language, and which language varieties are to be included in both cases, cannot be answered clearly. Kurds themselves are mostly of the opinion that “Kurdish” (Kurd. “kurdî) is a language with different dialects such as Kurmanji, Sorani, Zazaki and Gorani. However, if one reads the German or English Wikipedia article, one speaks of “Kurdish language s“; in the Kurmanji version of the same encyclopedia, however, Kurdish is described as a language with different dialects.

There is no consensus among linguists on how to distinguish between language and dialect. Probably the most widespread view on the distinction between language and dialect is based on the criterion of mutual intelligibility. According to this thesis, all mutually comprehensible language varieties are only dialects of one language, and not mutually comprehensible language varieties which can be assigned to independent languages. The following problem shows why even this demarcation criterion is not convincing and has therefore not led to a consolidated consensus: In a dialect continuum, i.e. in a chain of mutually understandable language varieties, a variety at the end of the dialect continuum could communicate with the adjacent variety or language outside the dialect continuum without the other language varieties within the dialect continuum being able to do the same. Thus, on the basis of the criterion of mutual comprehensibility, it is not possible to draw unambiguous boundary lines, but rather different boundary lines, which each classify language and dialect differently in relation to the chain of language varieties, but then these individual classifications in languages contradict each other. Therefore, there is no scientifically indisputable criterion for the demarcation between language and dialect. The question is therefore also whether the demarcation can be scientifically justified at all. It is probably not. The distinction between language and dialect is more often based on social or political reasons than on scientific reasons. For the same reasons, the choice of the designation of the language may also be omitted, e.g. if the language designation is intended to establish a connection with the ethnicity and/or the home country, the glossonym is to correspond to the ethnonym and/or the toponym (example: German – Germans – Germany). The classifications are therefore artificial and not natural.

It is possible that a person who understands only Low German (there are such people in the USA whose ancestors emigrated before the time of compulsory schooling) understands Dutch better than Bavarian German. Another example is Swedish, Norwegian and Danish: Sometimes two speakers of certain varieties of two of these languages understand each other better than two speakers of different varieties of one of these languages. Here we have the example that the classification of groups as ethnicities/nations by means of the criterion of language is constructed and thus artificial. This insight is recognized in the reputable social sciences (in the now prevailing constructivist approach, as opposed to primordialist), which contradicts many nationalist-ideological views. The best-known nationalism theorists in the world describe nations, and thus also ethnic groups in the case of ethnic nationalism, hence as “imagined communities” (Benedict Anderson) and “contingent” (Ernest Gellner), their emergence is based on “inventednd not predetermined by “the nature” of the language. The same even applies to other characteristics such as race, culture, ancestry, etc. traditions” (Eric Hobsbawm).

Kurdish nationalism, for example, has developed a narrative of an ethnic continuity of the Kurds that goes back thousands of years. The Ezidis are included as original Kurds (so-called “kurdên resen”) with a “Kurdish-speaking” religion, which did not accept Islam (thus a foreign element) and thus maintained the “original religion of the Kurds”. But the narrative of a common ethnic continuity is purely ideological construct for the legitimation of a nationalism. But today there are quite a few Ezidis who believe this narrative completely uncritically. Here it can be observed in an exemplary way how an ethnic self-definition of a group can be changed by an ideological narrative that has little in common with actual history. Or as Ernest Renan said on March 11, 1882 in his famous speech entitled “Qu’est-ce qu’une nation? (What is a Nation?): “Forgetting, I would even go so far as to say historical error, is a crucial factor in the creation of a nation, which is why progress in historical studies often constitutes a danger for [the principle] of nationality. ” In fact, in the period before the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, which coincided with the emergence of nationalism in the region, there were separate and independent ethnogeneses of the Kurds and Ezidis, cross-religious ethnic awareness was foreign to the zeitgeist, and the Ottoman Millet system also classified social groups according to religion. However, the ethnogenesis of the Ezidis is not to be traced on the basis of historically comprehensible facts. The main focus of this article is on language.

In the case of the Kurds, it can be noted that although among them the speakers of the various “Kurdish dialects”, such as Kurmanji, Zazaki, Sorani, Gorani, probably cannot easily communicate with each other in most cases, they regard all these varieties as dialects of one language, the Kurdish language. Or one tries to classify Lurian (Kurd. loranî): Own language, Kurdish dialect or Persian dialect? The criterion of mutual comprehensibility is often not fulfilled. But the diversity of a group does not necessarily exclude its character as an ethnic group or a nation. There are nations with more than one language, such as Switzerland. But even the use of the same language does not necessarily establish a common nation. Often different nations have the same language. So even if one assumes that there are different Kurdish languages (which the majority of Kurds do not), this does not exclude a common Kurdish nationality. On the other hand, it is not obligatory that groups that speak a common language with Kurds should be classified as part of the Kurdish nation or ethnic group.

According to what has just been said, the use of “Ezdiki” is not “wrong” in any sense. And Ezdiki also cannot be equated with Kurdish without further ado: On the one hand Kurdish cannot be clearly defined on the basis of objective criteria (since the delimitation of languages and dialects is often of a subjective nature), on the other hand different groups who speak the same language can certainly use different glossonyms. The only objective truth is that Kurmanji and Ezdiki refer to the same linguistic variety.

Êzdikî in the past and present

As mentioned, the glossonym “Ezdiki” is used today almost only by Ezidis from the post Soviet area. This raises the following questions: Which glossonyms beyond that have Ezidis used in the course of history till today? And what about the Ezidis from other areas?

Many Kurdish nationalists, among them above all older so-called “Kurdish-Ezidi intellectuals” (their name for this class, common among the other Ezidis), relentlessly attempted and still attempt that Ezidis use the term “Kurdi” (Kurdish) instead of the term “Ezdiki” (Ezidi). Especially since the collapse of the Soviet Union Ezdiki is considered as an officially recognized minority language in Armenia. Even state supported textbooks were printed in “Ezdiki”. There is no language called “Ezdiki”, so often their credo. That Armenia recognized “Ezdiki” as a language was the work of Armenian nationalists who wanted to divide the Kurdish people by ethnically separating the Ezidis from the remaining Kurds. And the Ezidis who agree with this policy are uneducated, ignorant and puppets of foreign interests. In this or a similar way there are statements by almost all “Kurdish-Ezidi intellectuals”.

Is that true? Did Armenians in the nineties of the 20th century invent the glossonym “Ezdiki” for political-ideological reasons and plant it on the Ezidis? This is clearly not the case. Anyone who is a participating observer among today’s post-Soviet Ezidis will find out that in their everyday life throughout the whole society the term “Ezdiki” is used. If one asks the older generation, without expressing a Kurdish nationalistic expectation to them, whether “Ezdiki” was also used during their childhood, thus long before Armenia’s independence, they will affirm it as self-evident. According to this also the previously mentioned “Kurdish -Ezidi intellectuals” from Armenia, who deny the existence of “Ezdiki” and fight against its use, should know the term “Ezdiki” from their childhood. And this is actually the case, but it is concealed. Christian sects, which after the fall of the Iron Curtain committed missionary work in the former Soviet Union, published a “Bible in Ezdiki”. That they did not choose “Kurmanji” or “Kurdi” in order to convert the Ezidis has its reason; that they hoped for greater success in missionizing because people were more familiar with “Ezdiki”.

In this context it is interesting to ask whether besides “Ezdiki” also “Kurdi” and “Kurmanji” were used in the Soviet Union, i.e. at a time when Ezidis lived for the first time in history in a state which made education possible for them and – to the extent historically unprecedented for the Ezidis – actively promoted cultural participation in their mother tongue. An extensive cultural heritage was left behind, which is still used today.

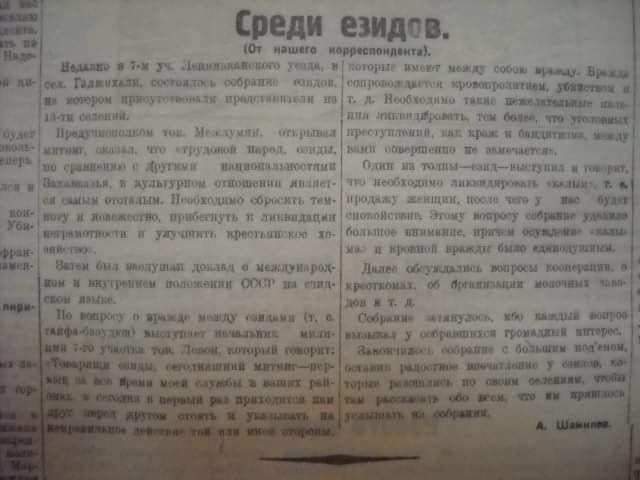

The early development can be illustrated by Arab Shamilov (Erebê Şemo). Arab Shamilov comes from an Ezidi sheikh family (Shekhobekir sheikhs within the Qatani lineage) and is historically known as the author of the first novel in Kurmanji. As late as 1926, Shamilov wrote in an article in a Russian Soviet newspaper: “Two Ezidi villages, Bolshoi and Maliy Mirak, have begun building a school for 80 pupils. It will be teached in the Ezidi language”. Arab Shamilov, the author of the first Kurmanji novel in history, speaks of an “Ezidi language”. In later years, and then continuously until the end of the Soviet Union, the language term “Ezdiki” disappeared from the public, Ezidis themselves used “Kurmanji” outwardly. The reason for this can be explained by Stalin’s nationality policy implemented in the 1930s.

After Stalin was commissioned by Lenin to examine the nationality question in the Soviet Union, Stalin wrote in 1913 that a common language was a characteristic feature of a nation. He mentions, however, that different nations can have the same language. According to him, Ezidis and Kurds would not necessarily have to form the same ethnic group. The anti-religious tendency of his socialist ideology suggests, however, that for him religious affiliation was not a criterion for establishing ethnicity or nation. Although he accepted the right to national self-determination; how nation was to be defined was to be determined from above in the manner most expedient to socialism. In this definition there was no place for religious affiliation as a characteristic. Ethno-religious identities, and thus also glossonyms related to an ethno-religious identity, were unwanted. This led to the disappearance of “Ezdiki” as a glossonym in public, in favour of Kurmanji or Kurdish. These changes in political circumstances also seem to have had an influence on Arab Shamilov and other authors; after 1930 he no longer used “Ezdiki”. The situation changed abruptly after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the revival of Armenian nationalism and Armenia’s independence.

Once again the political circumstances that influenced the Ezidis changed and continue to do so today. Muslim Kurds were no longer welcome in Armenia, because Armenia was in a warlike conflict over the Nagorno-Karabakh region against Azerbaijan and feared the loyalty of the Muslim Kurds with the Azerbaijanis mainly because of the common religion of Islam and the Armenians remembered the Muslim Kurds as participants in the execution of the Armenian genocide around 1915, almost all left Armenia. Furthermore, ideologisms of Armenian and Kurdish nationalism were now competing against each other. What “West Armenia” is for Armenians, “North Kurdistan” is for Kurds. For all these reasons there was a tendency in Armenia to weaken the “Kurdish factor” as much as possible. This was also contributed to by the policy of a separate Ezidi ethnic group. After the soviet nationality politics and the political activism of the Kurds in the 20th century tried to influence the Ezidis in one direction – that of Kurdification – there was now also a political force which tried to influence the Ezidis in the other direction. This situation led to serious tensions within the Ezidi community from Armenia, some of which took violent forms.

It should be noted that in Iraqi Kurdistan, for example, the Kurdification policy towards the Ezidis was and is much more radical than the Armenian policy, which was not based on coercion but only on proactive recognition policy. Today’s Kurdish media, especially in northern Iraq such as Rudaw or Kurdistan24 , are constantly trying to nationalistically implant the term “Ezidis” in order to achieve a suggestive effect; they almost never report on Ezidis without mentioning that they are Kurds. What consequences it can have if Ezidis in northern Iraq do not want to be defined as Kurds can be read in a Human Rights Watch report from 2009: Two members of the Ezidi party ISLAH, which propagates an independent Ezidi identity, were captured by Kurdish security forces (Asayiş) and tortured in interrogation. One of them was asked “What is your language?” during the interrogation, whereupon he replied “Ezdiki”. He was answered: “No, Ezidis have no language, they speak Kurdish”. As punishment he was taken away and tortured further (see link).

Science, too, is not ideology-free in this context of identity politics. In Armenia Orientalists use the term “Ezdiki”, which is a thorn in the side of many Kurdish authors. Western scientists, on the other hand, never use the term “Ezdiki” and always describe the Ezidis as “Kurdish”-speaking. This may well be due to the fact that Western scientists mainly came into contact with Kurdish nationalistically socialized people during their field research, so that they were under the influence of Kurdish nationalism, and this seems to be the case to this day. Both sides can be reproached here, since the task of scientists can only be to recognize how Ezidis really describe their languages, how they identify themselves, and precisely not how tey are portrayed by others or how it is more beneficial for other peoples’ narratives.

Today the glossonym “Ezdiki” is used mainly among the Ezidis from the former Soviet Union, but it is also gaining popularity in the Ezidi diaspora in Germany and in some parts of their settlement areas in Iraq. However, it is interesting that Ezidis who were not ancestors of Soviet Ezidis also used this glossonym. The accusation that Ezidis invented the term “Ezdiki” for ethnic differentiation from Kurds and that this term was promoted by the Armenian state goes ad acta. The anthropologist Ernest Chantre interviewed Ezidis in Birecik in present-day Turkey during his research trips in 1895. He reports as follows (translated from French):

“They both [Ezidis and Kurds] speak “Kourmandji.” The Ezidis call their language “zyman e ezda” (the language of the Ezidis), and they claim that it is the Kurds who speak their language, and not them who speak the language of the Kurds.”

(„Les uns et les autres parlent le «Kourmandji». Quoique les Yézidi appellent leur langue «zyman e ezda» (langue des Yézidi ) et prétendent que ce sont les Kurdes qui parlent leur langue, et non pas eux qui parlent la langue des Kurdes.“ (Ernest Chantre, „Notes ethnologiques sur les Yésidi“, 1895)).

So there were also Ezidis outside the Armenian sphere of influence who long before did not even want to use the term “Kurmanji” for their own language and preferred to speak of “the language of the Ezidis”. It is not surprising that the nationalistic narrative mentioned above does not pay attention to such sources. And science, too, has deliberately suppressed such sources to this day – there is no other way to explain it.

But it is also certain that many Ezidis used and still use the term “Kurmanji”. For Kurds and Ezidis alike, the following applies: The use of “Kurdi” (Kurdish) was only promoted in recent decades, especially by Kurdish television stations with a nationalist agenda – from today’s perspective very successfully. The use of “Kurmanji” was more common in the past. Today Kurmanji is perceived by Kurds as a dialect of the Kurdish language, which includes many other dialects such as “Sorani” or even “Zazaki”. Even though the Ezidis used to use “Kurmanji”, there is no verifiable etymological connection between the words “Kurmancî” and “Kurdî”. Attempts to establish such a connection have so far led to various, sometimes contradictory theories. One theory (MacKanzie) states that “Kurmanc” is a composition of “Kurd” for Kurd and “manc” for Meder. Another theory claims that “Kurmancî” is derived from the name of the city Kermanschah (Kurd. Kirmanşan). Nevertheless, today Ezidis sometimes use the word “Kurdi” when it is more useful for foreigners to understand.

Interesting at this point is also the fact that until today the term “Kurmanc” is used exclusively as a term for Muslim Kurds by a large part of the Ezidis. Kurmanc are mainly Kurmancî-speaking Kurds in Turkey and Syria. However, this endonym (self-designation) is still used today by Ezidis, although many of them define their language as Kurmancî and themselves as Kurds and lived with Muslim Kurds in the same area, exclusively as a different characteristic. This has historical, ethno-religious reasons that are hardly present in consciousness today.

It is also significant that today’s Ezidis, which were socialized Kurdish-nationalistically, do not oppose the historically relatively new proper designation “Kurdi” for Ezidis, but the historically longer used proper designation “Ezdiki”, arguing that “our language has always been “Kurdi” and that “Ezdiki” was reinvented to divide the Kurds”, i.e. almost the opposite of what is true, with an astonishing conviction. “Ezdiki” should not be used, but “Kurdi” instead and Ezidis should identify themselves as Kurds, after all Muslims do not speak “Muslim” either. The fact is that language designation does not follow any laws of nature or logic. Of course it is possible to call a language “Muslim”, even if there is no such language anywhere. But there is, for example, “Yiddish”, which is used as a glossonym by Jews and translates to “Jewish”. “Ezdiki” is thus not an isolated case. It probably plays a role that Islam and Christianity are religions with universal claim and strong spreading, therefore with the linguistic diversity a glossonym with borrowing from the religious denomination would not result in the ability to distinguish languages. But this is different with Jews and Ezidis.

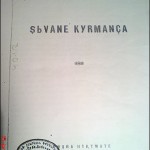

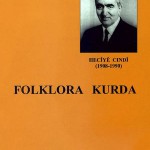

In this context, it is appropriate to illustrate two examples to see how attempts are being made to construct a nationalist narrative. Arab Shamilov (Êrebê Shemo), the author of the first novel in Kurmanji, gave this novel the title “Shivane kurmanca”, which can be translated as “The Shepherd of the Kurmanj”. Some Kurdish nationalists did not like this title. Because if “the first Kurdish novel in history” speaks only of “Kurmanj” and not of “Kurds”, this novel is less useful as a national symbol for the legitimation of Kurdish nationalism. So later, new editions of this book were printed with the title “Shivane kurda (The Shepherd of the Kurds). Another example: Heciye Cindî’s “Folklorê kurmanca” (The Folklore of the Kurmanj) was renamed “Folklorê kurda” (The Folklore of the Kurds).

The question arises why even certain intellectuals and politically active “Ezidi Kurds” vehemently fight the glossonym “Ezdiki”. Although even some of them, namely those from the former Soviet Union, must – what they themselves do not admit – be familiar with the term from their own childhood. The reason is their internalized Kurdish nationalist ideology. Ideology aims to change the will of others, in this case the promotion of a Kurdish national feeling through identity politics in the form of language politics. Through their nationalist-ideological delusion, they are denied access to objective knowledge. They cannot or will not accept that Ezidis use the term “Ezdiki” because there should only be “Kurdi”. Therefore those Ezidis are seen as simple, uneducated, ignorant and as puppets of the oppressors of the Kurdish people and thus traitors. They, on the other hand, regard themselves as the intellectual elite. In truth, this ideological delusion led to fascist tendencies and unreasonableness. Not a single Kurdish-Ezidi nationalist, for example, spoke out against the torture of Ezidi activists reported by Human Rights Watch because they share the same nationalist doctrine: Ezidis are Kurds and speak Kurdish. They are pure nationalist ideologues and almost completely ignorant and uneducated in nationalism theory and anthropology. Younger, more open-minded generations of the Ezidis increasingly have nothing but incomprehension for these persons and regard them as tragic figures in Ezidi history.

It is sometimes astonishing with what kind of dynamism especially intellectual circles of todays’ Ezidis try to either distort the history of their own ancestors in favor of seemingly nationalistic goals or even to deny it altogether, to reinterpret it and thus to falsify it. So to fight against an inheritance, against an identity for which the Ezidis are still paying with their lives, as the events of 2014 have shown once again.

© ÊzîdîPress, December 4, 2018