By Saad Babir

After gaining control of much of Iraq and Syria, the Islamic State jihadist movement (IS) and other Sunni extremists committed grave atrocities and international human rights violations against non-Sunni minorities, including perhaps the most extreme crime of all, the genocide that was perpetrated against Yazidis, Christians, and Shia Muslims. As IS is gradually defeated on the battlefield, another fear looms ahead for these persecuted groups.

After gaining control of much of Iraq and Syria, the Islamic State jihadist movement (IS) and other Sunni extremists committed grave atrocities and international human rights violations against non-Sunni minorities, including perhaps the most extreme crime of all, the genocide that was perpetrated against Yazidis, Christians, and Shia Muslims. As IS is gradually defeated on the battlefield, another fear looms ahead for these persecuted groups.

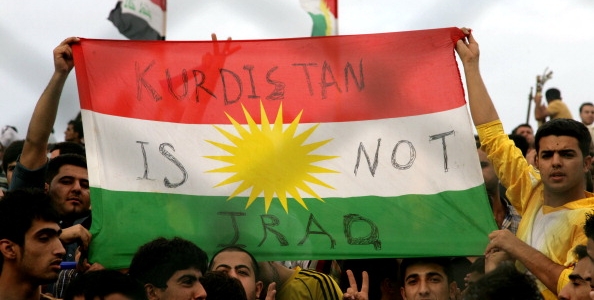

Despite the overwhelming objection of many international and local parties, the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) will mostly likely hold a referendum for independence on September 25 in the KRI’s official governorates of Erbil, Suleimaniyah, and Dohuk, as well as in the disputed territories of Kirkuk, Nineveh Plain, and Sinjar.

Ethnic and religious minorities inhabit the disputed territories, which are heterogeneous in population and present different concentrations of Iraqi minorities including Christians, Yazidis, Turkmen, Shabak, and Kakai—minorities that have long suffered threats and persecution. But today, they face another dilemma.

The minorities face two challenges: the potential for immediate danger ignited by the process of independence itself, and secondly, their rights being jeopardized under future separate states of Kurdistan and Iraq.

In the KRI, religious extremism has expanded significantly in the past ten years, paralleling the general increase in religiosity. The number of mosques in the region now exceeds the total number of schools, universities, and hospitals combined. Concerns that religious extremism could increase in the future causes alarm for non-Muslim groups. Studies have shown that around one thousand Kurdish youth joined IS, suggesting that Kurdish societies have serious issues with radicalism that must be addressed.

While the KRI is mainly ruled by nationalist parties that are not ideologically invested in Islamic beliefs, non-Muslim minorities fear that this might not hold in the future and that, as in other Middle Eastern countries, religious attitudes will eventually become dominant.

More importantly, the process of independence itself could be threatening to minorities, especially since the primary areas inhabited by minorities are located almost exclusively on the borders of the KRI, meaning that if Kurdish independence were to be resolved through military means, these areas would be the first to be hit by war. Not only would this delay the return of IDPs to Yazidi areas, but it could even make their return impossible.

Minorities in Kurdistan often claim that they are being used by the Kurdish political parties for political advantages. The referendum was designed to take place without input from the KRI minorities and their political opinions were not solicited. However, some groups have gone ahead and submitted written recommendations or demands. Assyrians, Armenians, and Turkmen have submitted a paper with fifty demands to the High Committee of the Referendum. These demands mainly ask that religious and ethnic rights to be preserved in the new state and emphasize that autonomous administration of their areas should be granted.

Yazidis, the largest ethno-religious minority, will also be participating in the referendum according to the KRG’s plans. Yazidis, like others, are divided on the issue of Kurdistan’s independence; however, most Yazidis will probably stay away from voting.

The Yazidi political elite close to the KDP have been involved in promoting the referendum; however, the general Yazidi public appear to be highly disengaged from the process and to largely reject the referendum on an emotional level.

The disconnect between the Yazidis and the KRG, specifically the KDP, is the result of widespread mistrust. Many Yazidis believe that when the KDP security forces withdrew from Sinjar in August 3, 2014, they abandoned their military obligation and civic responsibility to protect the area, thereby making it easy for IS to commit genocide against Yazidi civilians.

Yazidi support for Kurdistan independence will not be free; if the Kurdish leadership want Yazidis to be on their side, they must commit to serious steps including bringing those who abandoned Sinjar to justice, assuring Yazidis of their rights under the constitution, accepting Yazidis as a group with a full set of rights as an ethnicity and a religion, and guaranteeing autonomy for Yazidi areas in Sinjar and Sheikhan.

Religious groups are also concerned about the demographic changes to their homeland. Many areas that were once considered homelands for Christians, Yazidis, Shabak, and Kakai in the Nineveh Plain have been altered over the past ten years. Kurdish Muslims have systematically settled in these areas, pushing out the indigenous people. These changes continue today. For example, the percentage of Yazidis in the total population of the Sheikhan district, north of Mosul, was around 85 percent 30 years ago. Today, the ratio of Yazidis to Muslims has significantly decreased, with the percentage of Yazidis now estimated to be below 30 percent with Kurdish Muslims around 70 percent.

The Yazidi town of Bashiqa is experiencing similar demographic changes and other Yazidi areas have been (and will continue to be) impacted, as well. The Master Plan for the City of Dohuk, designed in 2010 by the Ingenieurbüro Vössing Germany—Erfur Company (intended to be completed by 2032), would turn Yazidi lands in the Shaariya plains south of Dohuk City into a new suburb of Dohuk. Shaariya is one of the last few Yazidi-majority areas inside the KRI.

The conversation surrounding Kurdish independence also ignores the demands of religious minorities to establish safe zones for their populations in Sinjar and Nineveh Plain under international protection, with the help of both the United Nations and the European Union. These demands can also take the form of self-administered local government and security forces to ensure the stability of minority areas without the meddling of external political parties. No matter how these desires are articulated, with the current political fight between the KRG and Iraq, it is unlikely that anyone will pay attention to the plight of minorities.

Minorities face two options: first, to be part of the State of Iraq, meaning they will have to co-exist and live with the Sunni Arabs encircling them. With a distant Baghdad, this option remains risky and uncomfortable for all non-Muslim minorities.

The second option is to accept the de facto control of the KRG and become part of a newly formed Kurdish State. With all of the challenges detailed in this article, it is clear that this option is also fraught with risks.

The sad plight of Iraq’s minorities today is that there is no clear path to security and survival. Without the concerted involvement of the international community, we may witness the continued decline of these populations, as they continue to emigrate from the country.

______________________________

Saad Babir has a bachelor’s degree from the University of Dohuk and has worked in the past as a journalist and human rights activist, especially concerned with issues facing the Yazidi component of Iraqi society. Saad lost his brother and two cousins in the attacks against the Yazidi people and now works to help survivors of the genocide. He hopes to contribute to efforts to prevent future genocides against minorities.